Happy New Year - President's Message 30/09

30/09/2016 12:18:05 AM

| Author | |

| Date Added | |

| Automatically create summary | |

| Summary |

In the two weeks since I returned from overseas, we have enjoyed wonderful Shabboses at South Head. First, new MP Julian Leeser spoke movingly about being the first Jewish Liberal member of Federal Parliament from New South Wales and about the death of his father 20 years ago; as Rabbi Milecki said, Julian is a proud Jew and a credit to our community. Then we had the Niasoff extravaganza: Levi’s bar mitzvah (where he read the Torah and haftarah and led the davening for Mussaf); the aufruf of Baruch, Yehoshua’s youngest brother (who got married in Melbourne the next day); and the birthday of Mrs Sophia Niasoff, Yehoshua’s mother – with celebrations enriched by our talented choir and a bountiful Kiddush. Last week Toby Port had his bar mitzvah, we honoured Malcolm Kofsky and Ian Charif for their long service to our shul through their appointment as life wardens, and we enjoyed a fantastic South African-themed Kiddush, including a creative little game park – great thanks to Bernice Charif, the mastermind of the event.

I have written to you and spoken in shul several times about how I see us as forming a big mishpacha, a family, where members care about and take an interest in one another. I believe this. In fact, I think that our success as kehilla is linked to how well we take this to heart.

As we near the holiest days of the year, Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur, I wish you and your families a happy, healthy and sweet New Year. It is an honour and privilege to serve you.

* * * * *

My Friend Ike

She is Holier Than Me

I could not have been more than 4 or 5 when I asked her. It seemed to me, at the time, to be an innocent, straightforward question: “Mummy, when do I get my number?”

I was, of course, upset when she burst into tears and ran out of the kitchen, but I was also confused. This was Washington Heights in the 1950s. It was an enclave of survivors. Every adult I knew had a number. Even my teenage sister had one in blue ink tattooed on her forearm.

They were as ubiquitous on the benches of Riverside Drive as they were on the footpaths of Fort Tryon Park. If you saw an adult with some sort of hat on his head, he invariably also had a number on his arm. In the summer, when the community traveled en masse to Catskill bungalow colonies, or to Rockaway beaches, the numbers came too. I presumed it was a ceremonious part of becoming bar mitzvah, or perhaps graduation from Breuer’s or Soloveichik, our local yeshivas. No one appeared to be embarrassed by their number. ARG! I never saw anyone try to cover it up when they went swimming. It seemed to be a matter of fact part of life.

When, as children, we would ask our parents why there was a “Mother’s Day” and a “Father’s Day,” but no “Children’s Day,” the automatic response was “Every day is ‘Children’s Day’!” In Washington Heights, in the ’50s, every day was Yom HaShoah.

Ironically enough, at the same time, no day was Yom HaShoah. The commemoration, as it exists today, was not around then. Breuer’s and Soloveichik consisted almost exclusively of children of survivors, yet neither school had any assembly, or recognition of any type, of the Shoah.

The very word Shoah didn’t exist. The word Holocaust did, but it was never invoked. When on rare occasion our parents would make reference to the events that led them to leave Europe to come to America, they would label it “the War.”

They spoke nostalgically of life “before the War”; they never spoke of what happened during “the War.” They spoke reverently of their parents and siblings who were “lost in the War”; they never spoke of their spouses or children who perished. After all, they had new spouses and new children who didn’t need to be reminded that they were replacements.

I was already bar mitzvah when I first realized that my parents had been previously married and had prior children. Years later I was shocked to discover that my sister with whom I was raised was not my father’s daughter.

When I finally came to understand that not every adult was a survivor, and people would ask me what survivors were really like, I never knew what to answer. There was Mr. Silverberg, our seatmate in shul, as jovial as Santa Claus, who always had a good word for everyone. On the other hand, there was Mr. Grauer, our neighbor whose face was indelibly etched in a frown and was always threatening to hit his wife or his children. In retrospect, as a psychiatrist, I could understand both, but who truly defined what it meant to be a survivor? Did anyone, or anything?

I learned the answer from Rabbi Moshe Feinstein.

This gadol hador, the greatest sage of his generation, was so renowned he was referred to simply as “Rav Moshe.” The closest I came to this legend was at Yeshiva University High School, where my rebbe was his son-in-law, Rabbi Moshe Tendler. Rabbi Tendler, and every other rabbi, would speak of Rav Moshe in awe-stricken tones usually reserved for biblical forefathers.

One summer I was spending a week with my aunt and uncle in upstate Ellenville. Uncle David and Aunt Saba, survivors themselves, as the doctor and nurse in charge of the concentration camp infirmary, had managed to save the lives of innumerable inmates, including my mother and sister. After “the War” they had set up a medical practice in this small Catskill village, where, I discovered, to my amazement, they had one celebrity patient — Rav Moshe.

My aunt mentioned casually that Rav Moshe had an appointment the next day. Would I like to meet him? Would I? It was like asking me, would I like to meet G-d.

I couldn’t sleep that night. I agonized over what I should wear. Should I approach him? What should I say? Should I mention that his son-in-law was my rebbe? Should I speak to him in English, or my rudimentary Yiddish?

I was seated in the waiting room, in the best clothing I had with me, an hour before his appointment. It seemed like an eternity, but eventually he arrived, accompanied by an assistant at each side. He didn’t notice me.

I was frozen. I had intended to rise deferentially when he entered, but I didn’t. I had prepared a few sentences that I had repeatedly memorized, but I sensed that my heart was beating too quickly for me to speak calmly.

My aunt had heard the chime when he entered and came out of the office to greet him: “Rabbi Feinstein, did you meet my nephew Ikey? Can you believe a shaygitz [unobservant] like me has a yeshiva bochur [student] in the family?”

Rav Moshe finally looked at me. I was mortified. My aunt was addressing him irreverently. She was joking with him. She had called me Ikey, not Yitzchok, or even Isaac.

Then it got even worse. She walked over to him. Surely she knew not to shake his hand. She didn’t. She kissed him affectionately on the cheek as she did many of her favorite patients. She then told him my uncle would see him in a minute and returned to the office.

Rav Moshe and his attendants turned and looked at me, I thought accusingly. I wanted to die. In a panic, I walked over to him and started to apologize profusely: “Rabbi Feinstein, I apologize. My aunt, she isn’t frum [religious]. She doesn’t understand...”

He immediately placed his fingers on my lips to stop me from talking. He then softly spoke two sentences in Yiddish that I will remember to my dying day: “She has numbers on her arms. She is holier than me.”

Rav Moshe had understood what I had not. Our holiest generation was defined by the numbers on their arms.

A Soloveichik Boy

I am a Soloveichik boy.

I am proud of it.

Growing up, that certainly was not the case. Soloveichik literally means “little songbird.” As a little bird, I was not singing its praises. I hated it so much I remember daydreaming, during my graduation in its ground-floor atrium, that if it inexplicably collapsed, the resultant carnage would merit front-page coverage.

For those who did not grow up in Washington Heights in the middle of the last century, let me explain that Soloveichik, more formally known as Yeshiva Rabbi Moses Soloveichik, was a short-lived, long-defunct elementary school located in an impressive building on 185th Street that now houses the Yeshiva University Cantorial School.

Though it was named for his father, the school had nothing to do with the most famous Soloveichik, “The Rov”, Rabbi Joseph Soloveichik. To the best of my knowledge, though he taught across the street for most of its existence, he never set foot in it.

Ironically, since The Rov was the greatest Talmudic scholar of his generation, Soloveichik was not particularly strong in Talmud. Most of us who crossed the street to Yeshiva University High School were, at first, placed in relatively low Talmud classes.

On the whole however, despite several addled teachers (in fifth grade we were inexplicably forced to memorize all the lyrics to Over The Rainbow) we received an excellent education. Our acceptance rate to select high schools, like Bronx Science, Hunter, and Stuyvesant was extraordinary.

Our greatest strength was in Hebrew. We were taught Ivrit B’Ivrit. We translated biblical Hebrew into Modern Hebrew. No matter where we went subsequently, as Soloveichik grads, we were ahead of the grade in Hebrew for the rest of our lives.

Then, why did I, and many of my classmates, not enjoy our years there?

It was a different era, particularly in the manner in which students were treated by faculty and administration.

Corporal punishment was a fact of life. One particularly fearsome Rebbe repeatedly warned us: “ I will smack you so hard your head will bounce off the wall like a Ping-Pong ball.” Ironically, he never struck us, but his colleagues did. I recall my friend Bitzy defensively assume a boxing pose when a particularly violent Rebbe approached.

What infuriated me more personally was the verbal abuse. Many teachers had obvious favorites, and equally apparent targets. I often fell in the latter category.

One English teacher took great delight in publicly deriding me. She automatically attributed any vandalism to me. When she was obligated to announce that I had received the highest grade on a standardized test, she made sure to add her opinion that I had undoubtedly cheated. She mocked my name, my clothing, my diction, and my eating habits. Even after I was no longer in her class, she’d come over to my table in the lunchroom to insult me.

I don’t know if other schools in that time were any better, but it’s easy to understand why I didn’t like it.

It’s harder to explain why, today, I am proud to be a Soloveichik boy.

One reason is that, though the school is no longer around, my class of 1963, fifty strong, is. Not only have we had four reunions (one in Israel), but also, thanks to the efforts of our class leader, who still lives in Washington Heights, we still stay in close touch. Our bodies may have aged, but our nicknames (Pee Wee, Iziu, et al.) have not.

As a result, though when I attended Soloveichik, I wasn’t friendly with any classmate who didn’t live in my neighborhood, today, I am. I’ve shared meals, and extended communications, with many. In the process, I’ve discovered a more important reason that I am now so proud to be an alumnus.

I never realized that almost all of my classmates were, like me, children of Holocaust survivors. We never spoke about it because our parents never did. The word Holocaust didn’t exist. When asked about the numbers on their arms, they replied that they received them in “the war.” When a substitute teacher wanted to discuss our grandparents, it never occurred to me why my classmates, like me, didn’t have any.

Soloveichik was a haven for the children of survivors. It defined the school. It was its Raison D’etre (a phrase I learned from our French teacher, Mrs. Strom.)

Recently, attending the funeral of, appropriately enough, Elie Wiesel, the gentleman sitting behindme remembered that we had previously sat together at a birthday party for Elie’s wife Marion. He didn’t recall my name, occupation, or any other detail, but one.

He said: “You’re a Soloveichik boy. Right?”

I replied: “Couldn’t be righter.”

To Kill A Hero: A Survivor’s Child confronts Go Set A Watchman

Do you love the name Atticus?

Most people do. It has increased in popularity for 15 consecutive years. In 2014, it was involuntarily bestowed upon 846 boys and 9 girls. This year, it was the single most popular name on the hip Nameberry.com. Actors Jennifer Love Hewitt, Casey Affleck, Mary-Louise Parker, Daniel Baldwin and Israeli heartthrob Oded Fehr all chose it for their children.

The reason is obvious. The American Film Institute voted that the greatest hero of American film was To Kill A Mockingbird’s Atticus Finch. Anyone who has ever read that iconic book, and we all willy-nilly have, has idolized him. The theme of a child belatedly discovering that their father was a hero resonates with all of us.

It is particularly compelling to children of survivors. As we grew up and discovered the reason that they had numbers branded on their arms and the horrifying truth of why they woke up screaming every night, we too belatedly discerned that our parents were heroes. In several columns I have written in this paper, I have called them “The Holiest Generation.” In a memoir I wrote about my father, I compared him to Atticus.

Recently however, after repeatedly insisting that she would never publish another book, Harper Lee released a sequel to Mockingbird entitled Go Set A Watchman. Given Mockingbird’s hallowed status, it instantaneously became its imprint’s biggest seller of all time. Its title derives from Isaiah 21:6: “For God has said unto me, go, set a watchman; let him declare what he sees.”

It also however, instantaneously precipitated controversy. Our beloved Atticus, based on Lee’s own father, is revealed to be an embittered, racist Ku Klux Klansman. Our hero has a side so ugly, it makes it hard to remember his previous nobility.

How disillusioning. How disheartening. How to explain this to thousands of young Attici? Some parents have already decided that they couldn’t. They changed their newborns’ names.

Unfortunately, this dilemma is also familiar to children of Holocaust survivors. Our parents might have been heroes for surviving, but that did not mean that they all consistently behaved heroically.

My childhood community in Washington Heights was all survivors. I witnessed first-hand that my father was not alone in beating my mother and me. Though he was the hardest of workers and the noblest of Jews whose religious observance, unlike most, was more real than apparent, as a parent, and a husband, he obviously left a great deal to be desired.

I have spent my entire life endeavoring, too often unsuccessfully, to emulate his many virtues, while attempting, even harder, to distinguish myself from him as a father and husband. To this day, whenever my children or wife say or do something that displeases me, my inveterate instinct is to stop speaking to them the same way that he gave us the silent treatment for days.

I have only managed to never indulge that impulse because, above all, I never want them to feel about me the way that I felt about him.

I have been set a watchman, declaring to my children what I have seen, and my determination not to follow in his footsteps. I know that I, and they, will be damned if I allow the sins of the father to be visited upon his succeeding generations.

In later years, my mother’s sister, a survivor herself, a heroic nurse in charge of the Jewish infirmary at Auschwitz, often observed that she never expected me to become a good father, or husband. It was less a compliment to me, and more a posthumous insult to my father.

It bothered me greatly, but I couldn’t complain. We both knew that what she said was true.

I started writing my memoir 20 years ago when my father passed. I have published over a dozen excerpts from it in this and other publications.

And yet, until this column, like Harper Lee, in Mockingbird, I have never revealed his ugly side. Perhaps more tellingly, like Harper Lee for years, I have never published the manuscript itself.

On the surface, I have had my pragmatic reasons: I have never had the time to aggressively pursue an agent or publisher. I have focused on my responsibilities as a parent, husband, physician and friend.

Might there be a more visceral reason beneath the surface?

Mockingbird’s title derives from Atticus’ lesson to his daughter Scout/Harper that it is a sin to kill a mockingbird.

Is that the real reason that neither Lee, nor her sister, ever chose to publish Watchman all these decades?

Is that the reason that I have no desire to read Watchman?

Isn’t it similarly a sin to kill a hero?

Fri, 19 September 2025

26 Elul 5785

Contact Us:

Today's Calendar

: 6:15am |

| Shacharis : 6:45am |

: 8:50am |

: 8:50am |

| Candle Lighting : 5:31pm |

| Mincha : 5:45pm |

| Mincha : 5:50pm |

| kabbalat Shabbat : 6:00pm |

| Kabbalat Shabbat : 6:00pm |

This week's Torah portion is Parshas Nitzavim

| Shabbos, Sep 20 |

Candle Lighting

| Friday, Sep 19, 5:31pm |

Havdalah

| Motzei Shabbos, Sep 20, 6:27pm |

Erev Rosh Hashana

| Monday, Sep 22 |

Full Calendar Here

Happy Jewish Birthday!

Friday 26 Elul

- Lauren Ehrlich

Saturday 27 Elul

- Byron Gordon

- Nadia Wolf

Sunday 28 Elul

- Ashleigh Cohn

- Georgia Cohn

We wish "Long Life" to:

Sunday 28 Elul

- Annette Fialkov for father, Issy Frank

- Rolene Fain for mother, Fanny Fain

Halachik Times

| Alos Hashachar | 4:36am |

| Earliest Tallis | 5:05am |

| Netz (Sunrise) | 5:50am |

| Latest Shema | 8:49am |

| Zman Tefillah | 9:50am |

| Chatzos (Midday) | 11:49am |

| Mincha Gedola | 12:19pm |

| Mincha Ketana | 3:19pm |

| Plag HaMincha | 4:34pm |

| Candle Lighting | 5:31pm |

| Shkiah (Sunset) | 5:49pm |

| Tzais Hakochavim | 6:14pm |

| More >> | |

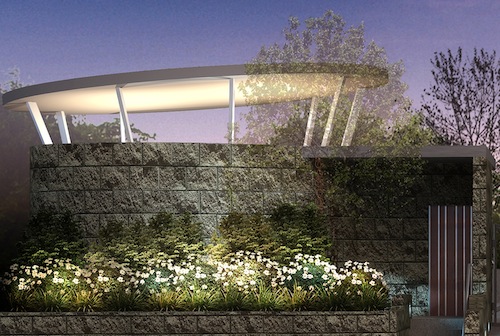

South Head Catering

South Head Catering is well and truly on the map! What began as a small initiative to provide a little variety and some new options by the South Head Ladies Guild has turned into a highly successful venture with people absolutely raving about the service and products on offer.

Want to know more? Want to help out and volunteer? Visit our Catering page.

Mikvah Aziza

Mikvah Aziza at 662 Old South Head Road, Rose Bay has re-opened.

Please click here for details:

South Head Library

Welcome to the Sandra Bransky Library & Youth Synagogue, located on the first floor and including the Beit Midrash. Drop in any Sunday morning between 9 - 11am.

Welcome to the Sandra Bransky Library & Youth Synagogue, located on the first floor and including the Beit Midrash. Drop in any Sunday morning between 9 - 11am.

I look forward to helping you get the most out of our beautiful world of books at South Head.

Sylvia Tuback, South Head Libarian

southheadlibrary@gmail.com

NITZAVIM

Rose Bay, NSW 2029

(02) 9371 7300

Privacy Settings | Privacy Policy | Member Terms

©2025 All rights reserved. Find out more about ShulCloud